The Queen’s Silver Jubilee 1977

© Martine Franck / Magnum Photos

I have to apologise for such a tardy review of an exhibition that has now been open several weeks. In truth, I have been thinking about it a lot since I walked round seven rooms of vintage photographs, which are on display at Tate Britain until the middle of this month. I have been trying to grapple with its purpose and meaning in the context of our national collection, a collection that, until recently, refused to stage a show of photographs at all, rebuffing them as a lower form of artistic endeavour. The Tate’s first exhibition solely dedicated to photographs was a mere 12 years ago, and before then it didn’t have an active acquisitions policy dedicated to photographs in their own right. Only those images, which fed into a wider artist’s practice (for example, Richard Long’s photographic documents of his walks and landscape interventions), were admitted, and even then, their purpose was purely to help explain the rest of the collection.

How things have changed. In fact, Another London marks something of a U-turn in Tate’s philosophy. Around 1400 photographs are being acquired for the nation, part gift and part purchase agreement with the owners, Eric and Louise Franck (the former, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s brother in law). The display reflects its illustrious owners, who still collect voraciously; the large majority of the prints on show are by Magnum photographers, though this may well reflect the agency’s domination of mid-century photo-reportage as much as it does the collectors’ partiality or ties to the group. Indeed, the show itself seeks to dissolve such biases, in displaying works only by foreign photographers, all coming to the central theme of London in individual ways. If you got to see the Museum of London’s street photography show a couple of years ago, the current display sits neatly as a kind of sister exhibition, looking repeatedly at London’s social milieu, its public spaces, and its private conversations, but this time from the point of view of outsiders looking in. Of the photographs being acquired, 177 are viewable at Tate Britain, highlighting some of the finest images of London to have been taken between 1930 and 1980. The survey starts with luscious, dense prints by visionaries such as Alvin Langdon Coburn, Bill Brandt, and Jacques-Henri Lartigue, and punctuates the medium with brash, highly posed punk portraits taken by Karen Knorr and Olivier Richon (how the dissenters consented…), and Leonard Freed’s monographic images of city dwellers in their own worlds.

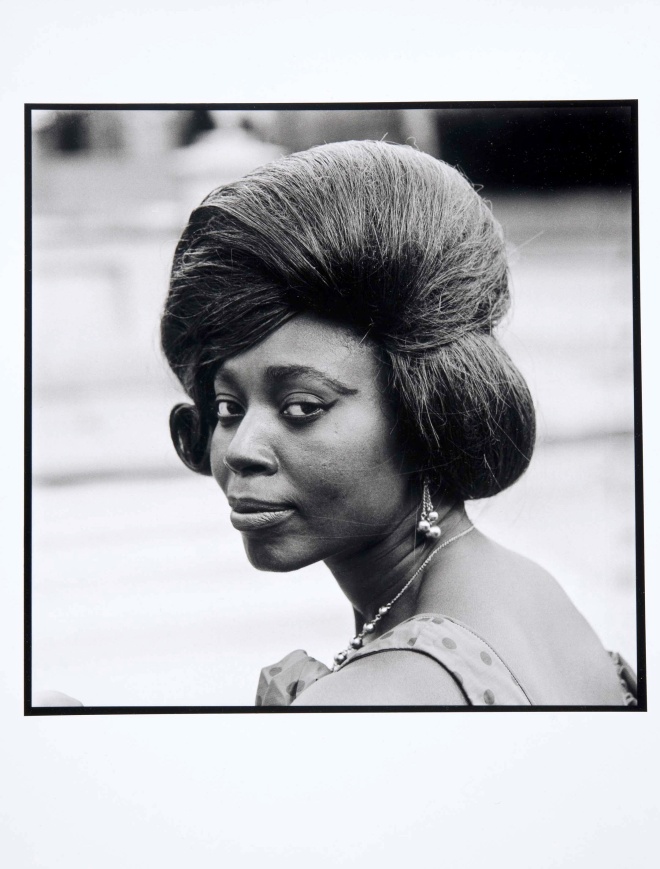

Eva, London circa 1960

© James Barnor / Autograph ABP

One of my favourites is Eva by Ghanaian born James Barnor (above), who set up a photography studio called Ever Young when he was just 21. The seductive curve of Eva’s eye, extended with a lick of black eye liner, makes her a pure study of beauty. Going back to another image right at the start of the exhibition, the same tone as Eva’s make-up draws murky figures from the grenadier guards out of the soot of London’s atmosphere. This wonderful photograph, entitled London, the changing of the guard, by Laure Albin-Guillot, is a fresson print. It uses charcoal to create tonal abysses and black-brown shadows on the warm buff-coloured paper beneath. Other images, snapping coolly at the hubbub and chaos of London streets, corner house tearooms, and grand parades, are so heavy with soft nostalgia that one yearns to have been present in their scenes, however unsettled or in crisis the moments they capture really were. Take the ménage of sexual games being played in Wolfgang Suschitzky’s Lyons Corner House, Tottenham Court Road for example, with its nonchalant sitter bored by her male companion’s obviously lack-lustre conversational efforts. His shoulders drop, his cigarette hangs as limply from his mouth as her attention to his advances does in the air, and her eyes seem to look past him as though to another, more attractive option.

Kenneth Williams argued that a critic’s greatest responsibility was to communicate enthusiasm for the art they belong to. It is easy to forget such a crucial mantra at times, but I myself cannot find a single fault with the beautiful works on display in this exhibition, though personally I prefer the carefully developed, striven over images that mark the earlier decades represented in the show; those rare survivals and experimentations with speed, unrestrained activity, and the contrapuntal imagery of disparate classes melded together in the city streets. In this respect, it was an easy show to put on, I imagine. The curators could have just chosen their favourites from an unsurpassable collection of images for all we know, and the show would be a complete success. Or maybe there were too many good ones, and the choices they had to make were thus excruciatingly difficult. Even without seeing the rest of the collection, I would probably lean towards the latter…

Having said I am in love with the show, I must concede that the labelling system the curators have employed infuriates me to the point of distraction. With so many images on display, a lot of them not often seen before, it is frustrating that one must walk to a corner of a large room in order to try and decipher a grid-like group of labels that seem to bear little relation to a raft of 10 or more images stretching away across the walls. I cannot see what they must have thought would be distracting about putting individual labels under each work. After all, if it is for purity’s sake that they chose to relegate all information to the corners of each wall, then why use such bulky black frames around every photograph? They tend to unify everything, which concatenates the labelling issue further, especially when you’re never quite sure whether the next set of labels will pertain to images on your left or right as you walk round in a heady daze. The frames’ tendency towards overall grouping is of course an understandable aesthetic aim, since the show attempts to broker a delicate line between presenting individual works, while nevertheless retaining the overall structure and nature of their relationships; the fact that they are from a single collection. Archivy and curation seem to rub shoulders quite succinctly and simply I must admit, if also a little heavy-handedly. Still, within the display, no effort is made to discuss format either, which changes so dramatically across the works. Why is a Robert Frank landscape view treated uniformly the same as a Marc Riboud or a Cartier-Bresson? For those of us with less knowledge of photographic history, the tendency of the framing and labelling choices to unify whole sections of rather distinct works, make it often difficult to remember who took what after you’ve left the exhibition.

Regardless of this, the way in which the final room’s display of photographs open up and shatter chronology is very well achieved, and one gets the sense that the images here start to sound; they rise in volume and express an ongoing cacophonic activity fostered by, and created within, our rolling capital. Suddenly, a course charted through immigrant photography in the twentieth century has the distinct possibility of fragmenting into many different paths.

Therefore, my only real reservation about Another London is how its contents, and the rest of the acquisition, are to be used in the future. Has the whole thing been a necessary, and as a result, staged part of the bequest procedure, without serious consideration of the next step? How will these images now be integrated into the rest of the collection, or will they come to reside for a few weeks at a time, as continues to be the case with many photograph shows, in a separate room of Tate Modern? This show has created some urgent questions about the strengths of our national collection, and how it is represented to us. Of course, we must wait and see how many other photographic collections are acquired by Tate over the coming years, but I am sure they will have to be pretty significant to match the roster of works represented in this astounding gift.